Squish for macOS Tutorials

Learn how to test native macOS applications.

- Tutorial: Starting to Test macOS Applications

- Tutorial: Designing Behavior Driven Development (BDD) Tests

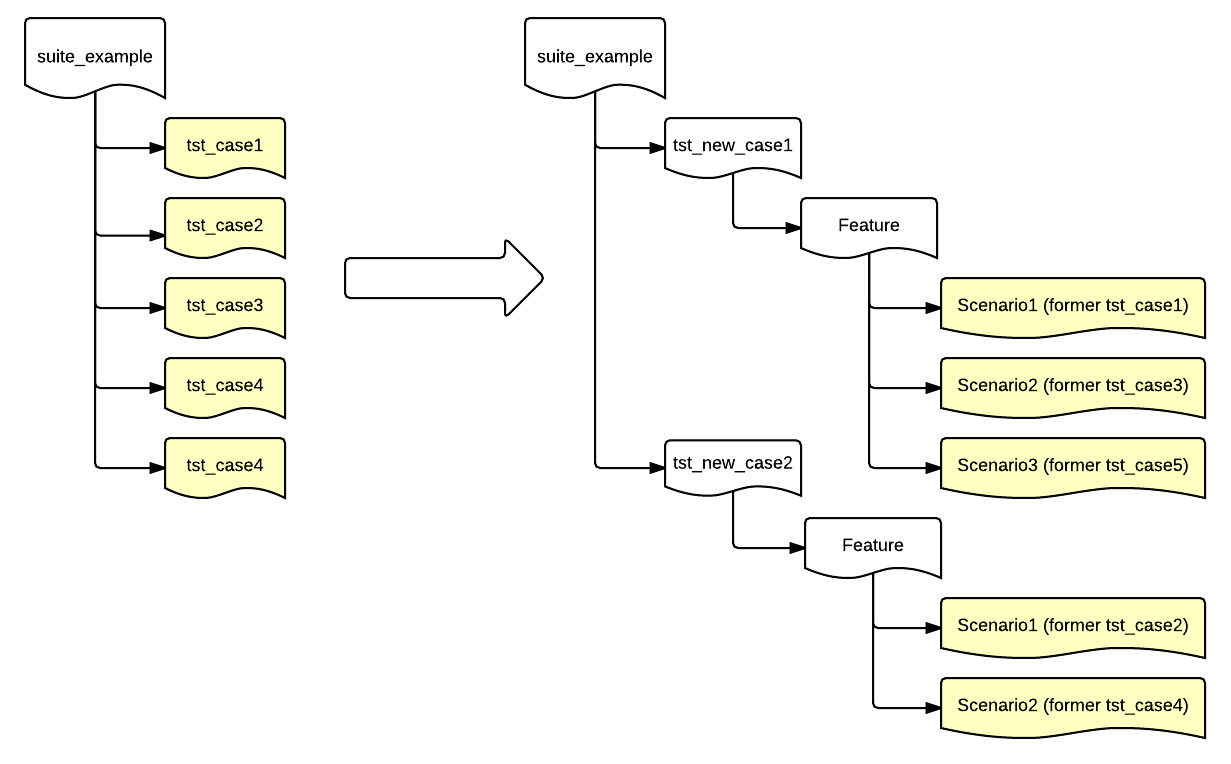

- Tutorial: Migration of existing tests to BDD

Tutorial: Starting to Test macOS Applications

Note: There is a 45-minute Online course about Squish Basic Usage at the  if you desire some video guidance.

if you desire some video guidance.

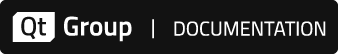

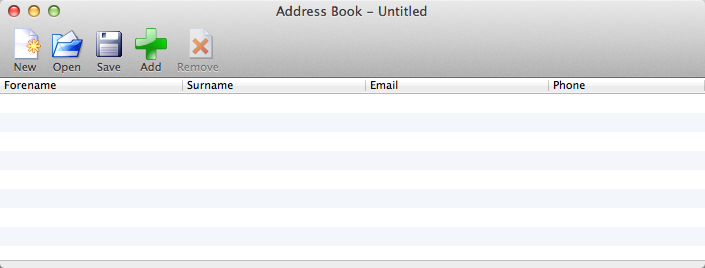

For this chapter, we will use a simple address book application as our AUT. The application is shipped with Squish in <SQUISHDIR>/examples/mac/addressbook. This is a very basic Cocoa application that allows users to load an existing address book or create a new one, add, edit, and remove entries, and save (or save as), the new or modified addressbook. Despite the application's simplicity, it has all the key features that most standard applications have: a menu bar with pull down menus, a toolbar, and a central area—in this case showing a table. It supports in-place editing and also has a sheet for adding items. All the ideas and practices that you learn to test this application can easily be adapted to your own applications. For more examples of testing various Cocoa-specific features, see How to Create Test Scripts.

The screenshot shows the application with a newly created, empty address book.

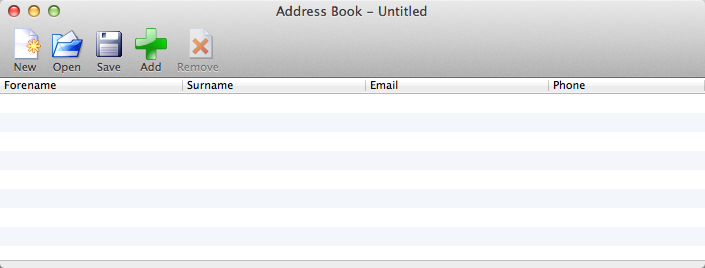

Squish Multi-Process Architecture and IPC

Squish runs a small server, squishserver, that handles the communication between the AUT and the test script. The test script is executed by the squishrunner tool, which in turn connects to squishserver. squishserver starts the instrumented AUT on the device, which starts the Squish Hook. With the hook in place, squishserver can query AUT objects regarding their state and can execute commands on behalf of squishrunner. squishrunner directs the AUT to perform whatever actions the test script specifies.

All the communication takes place using network sockets which means that everything can be done on a single machine, or the test script can be executed on one machine and the AUT can be tested over the network on another machine.

The following diagram illustrates how the individual Squish tools work together.

Tests can be written and executed using the Squish IDE, in which case squishserver is started and stopped automatically, and the test results are displayed in the Squish IDE's Test Results view. The following diagram illustrates what happens behind the scenes when the Squish IDE is used.

Under the covers, squishrunner is used to execute test cases. If we need to automate the execution of test cases from a script, we would use this command directly.

Creating Test Suites from Squish IDE

Start up the Squish IDE, by clicking or double-clicking the Squish IDE icon, by launching Squish IDE from the taskbar menu or by executing squishide on the command line, whichever you prefer and find suitable for the platform you are using.

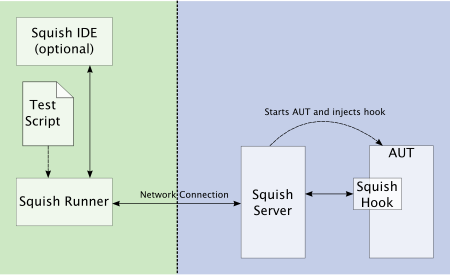

Once Squish starts up, you might be greeted with a Welcome Page. Click the Workbench button in the upper right to dismiss it. Then, the Squish IDE will look similar to the screenshot.

Creating Test Suites from Squish IDE

Start up the Squish IDE, by clicking or double-clicking the Squish IDE icon, by launching Squish IDE from the taskbar menu or by executing squishide on the command line, whichever you prefer and find suitable for the platform you are using.

Once Squish starts up, you might be greeted with a Welcome Page. Click the Workbench button in the upper right to dismiss it. Then, the Squish IDE will look similar to the screenshot.

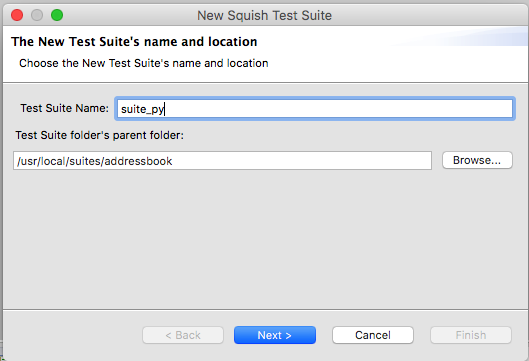

Once Squish has started, click File > New Test Suite to pop-up the New Test Suite wizard shown below.

Enter a name for your test suite and choose the folder where you want the test suite to be stored. In the screenshot we have called the test suite suite_py and will put it inside the addressbook folder. (For your own tests you might use a more meaningful name such as "suite_addressbook"; we chose "suite_py" because for the sake of the tutorial we will create several suites, one for each scripting language that Squish supports.) Naturally, you can choose whatever name and folder you prefer. Once the details are complete, click Next to go on to the Toolkit (or Scripting Language) page.

If you get this wizard page, click the toolkit your AUT uses. For this example, we must click Mac since we are testing a macOS application. Then click Next to go to the Scripting Language page.

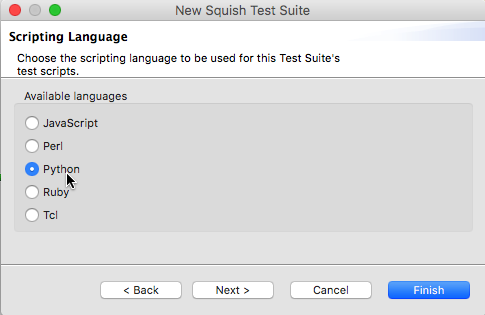

Choose whichever scripting language you want—the only constraint is that you can only use one scripting language per test suite. (So if you want to use multiple scripting languages, just create multiple test suites, one for each scripting language you want to use.) The functionality offered by Squish is the same for all languages. Having chosen a scripting language, click Next once more to get to the wizard's last page.

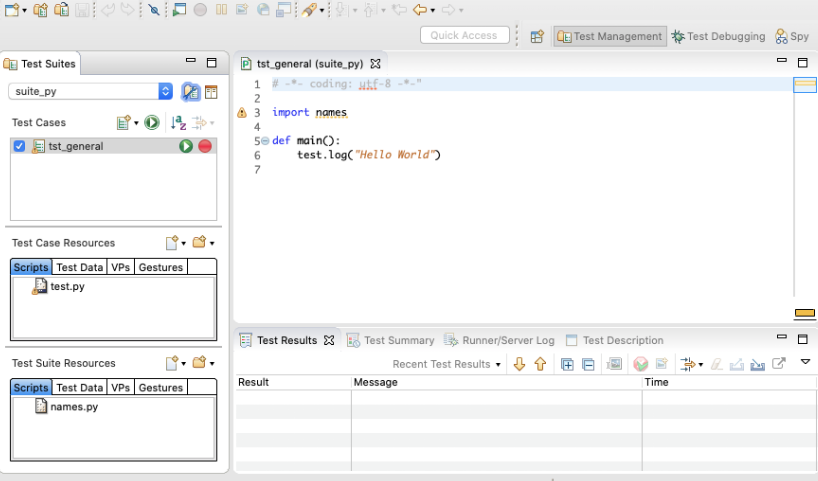

If you are creating a new test suite for an AUT that Squish already knows about, simply click the combobox to drop-down the list of AUTs and choose the one you want. If the combobox is empty or your AUT isn't listed, click the Browse button to the right of the combobox—this will pop-up a file open dialog from which you can choose your AUT. In the case of Cocoa programs, the AUT is the application's executable (e.g., SquishAddressBook on macOS). Once you have chosen the AUT, click Finish and Squish will create a sub-folder with the same name as the test suite, and will create a file inside that folder called suite.conf that contains the test suite's configuration details. Squish will also register the AUT with the squishserver. The wizard will then close and Squish IDE will look similar to the screenshot below.

We are now ready to start creating tests. Read on to learn how to create test suites without using the Squish IDE, or skip ahead to Recording Tests and Verification Points.

Creating Test Suites from Command Line

To create a new test suite from the command line:

- Create a new directory to hold the test suite—the directory's name should begin with

suite_. In this example we have created the <SQUISHDIR>/examples/mac/addressbook/suite_pydirectory for Python tests. (We also have similar subdirectories for other languages but this is purely for the sake of example, since normally we only use one language for all our tests.) - Register the AUT with the squishserver.

Note: Each AUT must be registered with the squishserver so that test scripts do not need to include the AUT's path, thus making the tests platform-independent. Another benefit of registering is that AUTs can be tested without the Squish IDE — for example, when doing regression testing.

This is done by executing the squishserver on the command line with the

--configoption and theaddAUTcommand. For example, assuming we are in the <SQUISHDIR> directory on macOS:squishserver --config addAUT SquishAddressBook \ SQUISHDIR/examples/mac/addressbook

We must give the

addAUTcommand the name of the AUT's executable and—separately—the AUT's path. In this case the path is to the executable that was added as the AUT in the test suite configuration file. For more information about application paths, see AUTs and Settings, and about the squishserver's command line options see squishserver. - Create a plain text file (ASCII or UTF-8 encoding) called

suite.confin the suite subdirectory. This is the test suite's configuration file, and at the minimum it must identify the AUT, the scripting language used for the tests, and the wrappers (i.e., the GUI toolkit or library) that the AUT uses. The format of the file iskey=value, with one key–value pair per line. For example:AUT = SquishAddressBook LANGUAGE = Python WRAPPERS = Mac OBJECTMAPSTYLE = script

The AUT is the Cocoa executable registered during the previous step. The LANGUAGE can be set to whichever one you prefer—currently Squish is capable of supporting JavaScript, Python, Perl, Ruby, and Tcl. The WRAPPERS should be set to Mac.

Recording Tests and Verification Points

Recordings are made into existing test cases. You can create a New Script Test Case in the following ways:

- Select File > New Test Case to open the New Squish Test Case wizard, enter the name for the test case, and select Finish.

- Click the New Script Test Case (

) toolbar button to the right of the Test Cases label in the Test Suites view. This creates a new test case with a default name, which you can easily change.

) toolbar button to the right of the Test Cases label in the Test Suites view. This creates a new test case with a default name, which you can easily change.

Give the new test case the name tst_general.

Squish automatically creates a sub-folder inside the test suite's folder with this name and also a test file, for example test.py. If you choose JavaScript as the scripting language, the file is called test.js, and correspondingly for Perl, Ruby, or Tcl.

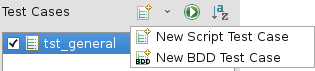

If you get a sample .feature file instead of a "Hello World" script, click the arrow left of the Run Test Suite ( ) and select New Script Test Case (

) and select New Script Test Case ( ).

).

To make the test script file (such as, test.js or test.py) appear in an Editor view, click or double-click the test case, depending on the Preferences > General > Open mode setting. This selects the Script as the active one and makes visible its corresponding Record ( ) and Run Test Case (

) and Run Test Case ( ) buttons.

) buttons.

The checkboxes are used to control which test cases are run when the Run Test Suite ( ) toolbar button is clicked. We can also run a single test case by clicking its Run Test Case (

) toolbar button is clicked. We can also run a single test case by clicking its Run Test Case ( ) button. If the test case is not currently active, the button may be invisible until the mouse is hovered over it.

) button. If the test case is not currently active, the button may be invisible until the mouse is hovered over it.

Initially, the script's main() function logs Hello World to the test results.

Once the new test case has been created, we are free to write test code manually or to record a test. Clicking on the test case's Record ( ) button replaces the test's code with a new recording. Alternatively, you can record snippets and insert them into existing test cases, as instructed in How to Edit and Debug Test Scripts.

) button replaces the test's code with a new recording. Alternatively, you can record snippets and insert them into existing test cases, as instructed in How to Edit and Debug Test Scripts.

Creating Tests from Command Line

To create a new test case from the command line:

- Create a new subdirectory inside the test suite directory. For example, inside the <SQUISHDIR>

/examples/mac/addressbook/suite_pydirectory, create thetst_generaldirectory. - Inside the test case's directory create an file called

test.py(ortest.jsif you are using the JavaScript scripting language, and similarly for the other languages).

Recording Our First Test

Before we dive into recording let's briefly review our very simple test scenario:

- Open the

MyAddresses.adraddress file. - Navigate to the second address and then add a new name and address.

- Navigate to the fourth address (that was the third address) and change the surname field.

- Navigate to the first address and remove it.

- Verify that the first address is now the new one that was added.

We are now ready to record our first test. Click the Record ( ) to the right of the

) to the right of the tst_general test case shown in the Test Suites view's Test Cases list. This will cause Squish to run the AUT so that we can interact with it. Once the AUT is running perform the following actions—and don't worry about how long it takes since Squish doesn't record idle time:

- Click File > Open, and once the file dialog appears, press Shift+ +Command+g and enter the

MyAddresses.adrfilename in the line edit that appears, then click the Go button, then click the Open button. - Click the first row, then click the Add toolbar button, then in the Add sheet's first line edit type in "Jane". Now click (or tab to) the second line edit and type in "Doe". Continue similarly, to set an email address of "jane.doe@nowhere.com" and a phone number of "555 123 4567". Don't worry about typing mistakes—just backspace delete as normal and fix them. Finally, click the Add button. There should now be a new second address with the details you typed in.

- Double-click the fourth row's second (surname) column, delete its text and replace it with "Doe". (You can do this simply by overtyping, then pressing Enter.)

- Click the first row, then click the Remove toolbar button and then click the Remove button in the message box. The first row should be gone, so your "Jane Doe" entry should now be the first one.

- In the Squish Control Bar, click the Verify (

) toolbar button and select Properties from the drop-down menu.

) toolbar button and select Properties from the drop-down menu.

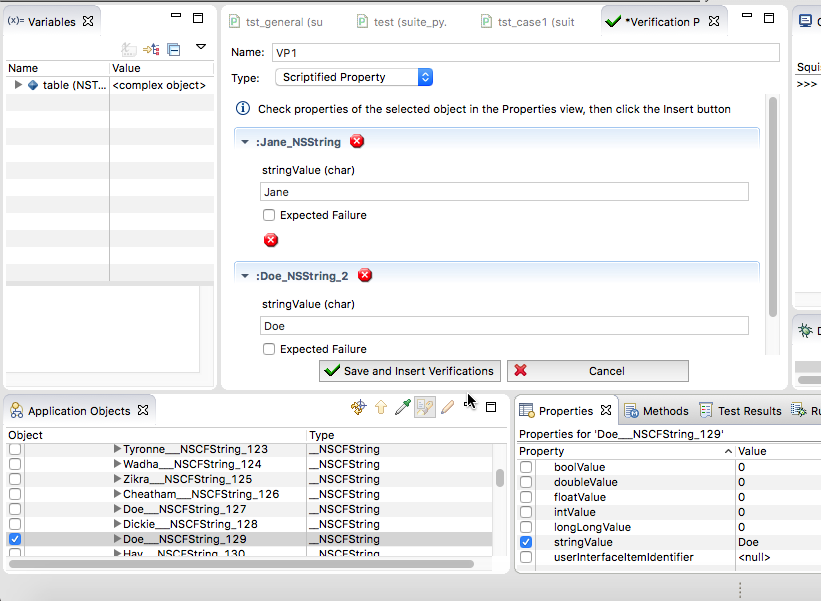

This will make the Squish IDE appear, and the central widget should show you a Verification Point Creator view. Before selecting any properties, make sure the Type of the VP is Scriptified Property, as shown in the following screenshots.

In the Application Objects view, expand the

Address Book - MyAddresses.adr_NSWindow_0object, then theNSView_0object, then theNSScrollView_0object, then theNSClipView_0object, and then theNSTableView_0object. Click theJane_NSCFString_0object to make its properties appear in the Properties view, and then check thestringValueproperty's checkbox. Now scroll down and click theDoe_NSCFString_127object and check itsstringValueproperty. Finally, click the Save and Insert Verifications button (at the bottom of the Verification Point Creator) to have the forename and surname verifications for the first row inserted into the recorded test script. (See the screenshot below.) Once the verification points are inserted, the Squish IDE's window will be hidden again and the Control Bar window and the AUT will be back in view.

Save and Insert Verifications button (at the bottom of the Verification Point Creator) to have the forename and surname verifications for the first row inserted into the recorded test script. (See the screenshot below.) Once the verification points are inserted, the Squish IDE's window will be hidden again and the Control Bar window and the AUT will be back in view. - We've now completed the test, so in the AUT click SquishAddressBook > Quit, then click Don't Save in the message box, since we don't want to save any changes.

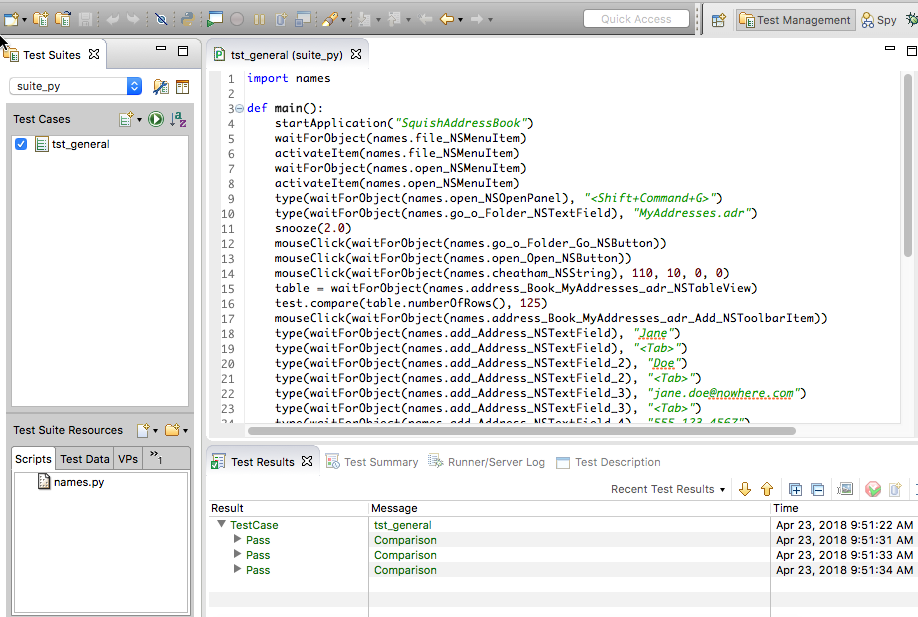

Once we quit the AUT, the recorded test will appear in Squish IDE as the screenshot illustrates. (Note that the exact code that is recorded will vary depending on how you interact. For example, you might invoke menu options by clicking them or by using key sequences—it doesn't matter which you use, but since they are different, Squish will record them differently.)

If the recorded test doesn't appear, click (or double-click depending on your platform and settings) the tst_general test case; this will make Squish show the test's test.py file in an editor window as shown in the screenshot.

Now that we've recorded the test we are able to play it back, i.e., run it. This in itself is useful in that if the play back failed it might mean that the application has been broken. Furthermore, the two verifications we put in will be checked on play back as the screenshot shows.

Inserting verification points during test recording is very convenient. Here we inserted two in one go, but we can insert as many as we like as often as we like during the test recording process. However, sometimes we might forget to insert a verification, or later on we might want to insert a new verification. We can easily insert additional verifications into a recorded test script as we will see in the next section, Inserting Additional Verification Points.

Running Tests from IDE

To run a test case in the Squish IDE, click the Run Test Case ( ) that appears when the test case is hovered or selected in the Test Suites view.

) that appears when the test case is hovered or selected in the Test Suites view.

To run two or more test cases one after another or to run only the selected test cases, click Run Test Suite ( ).

).

Running Tests from Command Line

To playback a recorded test from the command line, we execute the squishrunner program. We provide squishrunner the path to a test suite, and optionally also the name of a test case.

A squishserver must be running when running a test, and we can provide squishrunner an IP/Port of an already running one, or use the --local option which creates one for the duration of the process. For more information, see squishserver.

For example, assuming we are in the directory that contains the test suite's directory:

squishrunner --testsuite suite_py --testcase tst_general --local

Examining the Generated Code

If you look at the code in the screenshot (or the code snippet shown below) you will see that it consists of lots of Object waitForObject(objectOrName) calls as parameters to various other calls such as activateItem(objectOrName), mouseClick(objectOrName), and type(objectOrName, text). The Object waitForObject(objectOrName) function waits until a GUI object is ready to be interacted with (i.e., becomes visible and enabled), and is then followed by some function that interacts with the object. The typical interactions are activate (pop-up) a menu, click a menu option or a button, or type in some text.

The generated code is about 35 lines of code. Here's an extract that just shows how Squish records clicking the Add toolbar button, typing in Jane Doe's details into the Add sheet, and clicking Add at the end to close the sheet and update the table.

mouseClick(waitForObject(names.address_Book_MyAddresses_adr_Add_NSToolbarItem))

type(waitForObject(names.add_Address_NSTextField), "Jane")

type(waitForObject(names.add_Address_NSTextField), "<Tab>")

type(waitForObject(names.add_Address_NSTextField_2), "Doe")

type(waitForObject(names.add_Address_NSTextField_2), "<Tab>")

type(waitForObject(names.add_Address_NSTextField_3), "jane.doe@nowhere.com")

type(waitForObject(names.add_Address_NSTextField_3), "<Tab>")

type(waitForObject(names.add_Address_NSTextField_4), "555 123 4567")

mouseClick(waitForObject(names.add_Address_Add_NSButton)) mouseClick(waitForObject(names.addressBookMyAddressesAdrAddNSToolbarItem));

type(waitForObject(names.addAddressNSTextField), "Jane");

type(waitForObject(names.addAddressNSTextField), "<Tab>");

type(waitForObject(names.addAddressNSTextField_2), "Doe");

type(waitForObject(names.addAddressNSTextField_2), "<Tab>");

type(waitForObject(names.addAddressNSTextField_3), "jane.doe@nowhere.com");

type(waitForObject(names.addAddressNSTextField_3), "<Tab>");

type(waitForObject(names.addAddressNSTextField_4), "555 123 4567");

mouseClick(waitForObject(names.addAddressAddNSButton)); mouseClick(waitForObject($Names::address_book_myaddresses_adr_add_nstoolbaritem));

type(waitForObject($Names::add_address_nstextfield), "Jane");

type(waitForObject($Names::add_address_nstextfield), "<Tab>");

type(waitForObject($Names::add_address_nstextfield_2), "Doe");

type(waitForObject($Names::add_address_nstextfield_2), "<Tab>");

type(waitForObject($Names::add_address_nstextfield_3), "jane.doe\@nowhere.com");

type(waitForObject($Names::add_address_nstextfield_3), "<Tab>");

type(waitForObject($Names::add_address_nstextfield_4), "555 123 4567");

mouseClick(waitForObject($Names::add_address_add_nsbutton)); mouseClick(waitForObject(Names::Address_Book_MyAddresses_adr_Add_NSToolbarItem))

type(waitForObject(Names::Add_Address_NSTextField), "Jane")

type(waitForObject(Names::Add_Address_NSTextField), "<Tab>")

type(waitForObject(Names::Add_Address_NSTextField_2), "Doe")

type(waitForObject(Names::Add_Address_NSTextField_2), "<Tab>")

type(waitForObject(Names::Add_Address_NSTextField_3), "jane.doe@nowhere.com")

type(waitForObject(Names::Add_Address_NSTextField_3), "<Tab>")

type(waitForObject(Names::Add_Address_NSTextField_4), "555 123 4567")

mouseClick(waitForObject(Names::Add_Address_Add_NSButton))As you can see the tester used the keyboard to tab from one text field to another and clicked the Add button using the mouse rather than with a key press. If the tester had clicked the button any other way (for example, by pressing Enter), the outcome would be the same, but of course Squish will have recorded the actual actions that were taken.

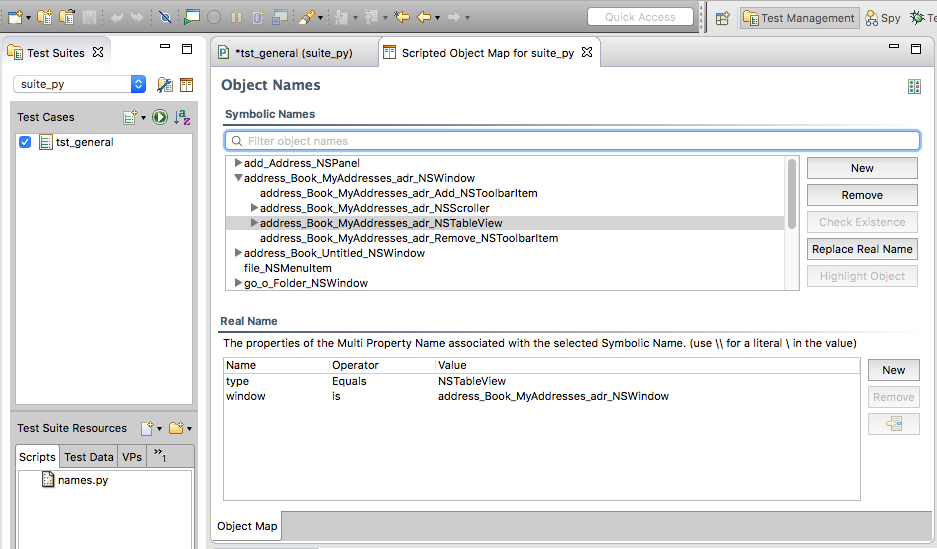

Symbolic Names

Squish recordings refer to objects using variables that begin with a names. prefix. These are known as Symbolic Names. Each variable contains, as a value, the corresponding Real Name.

The advantage of using symbolic names (instead of real names) in your scripts, is that if the application changes in a way that results in different names being needed, it is possible to update Squish's Object Map and thereby avoid the need to change our test scripts.

When a Symbolic Name is under the cursor, the editor's context menu allows you to Open Symbolic Name, showing its entry in the Object Map, or Convert to Real Name, which places an inline mapping in your script language at the cursor, allowing you to hand-edit the properties in the script itself.

See How to Identify and Access Objects for more details.

Now that we have seen how to record and play back a test and have seen the code that Squish generates, let's go a step further and make sure that at particular points in the test's execution certain conditions hold.

Verification Points Explained

In the previous section we saw how easy it is to insert verification points during the recording of test scripts. They can be inserted into existing test scripts by recording snippets, or by editing a test script and calling Squish's test. functions such as test.compare() and test.verify().

Squish can verify different kinds of data:

- Properties VPs, which can be Scriptified or XML-based. They verify that 1 or more properties of 1 or more objects have certain values.

- Table VPs, which verify the contents of an entire table.

- Screenshot VPs, for verifying images of widgets.

- Visual VPs, which contain properties and screenshots for an entire tree of objects.

Note: Image Search, a newer feature of Squish, is recommended as another way to verify images.

Regular Verification Points are stored as XML files in the test case or test suite resources, and contain the value(s) that need to be compared. This includes images in the case of Screenshot or Visual VPs. These verification points can be reused across test cases, and can verify many values in a single line of script code.

Scriptified Property Verification points are direct calls to the test.compare function and look like regular script code.

Further reading: How to Create and Use Verification Points.

Before asking Squish to insert verification points, it is best to make sure that we have a list of what we want to verify and when. There are many potential verifications we could add to the tst_general test case, but since our concern here is simply to show how to do it, we will only do two—we will verify that the "Jane Doe" entry's email address and phone number match the ones entered, and put the verifications immediately after the ones we inserted during recording.

To insert a verification point using the Squish IDE we start by putting a break point in the script (whether recorded or manually written—it does not matter to Squish), at the point where we want to verify.

As the above screenshot shows, we have set a breakpoint near the end of the script. This is done simply by double-clicking, or selecting Add Breakpoint after bringing up the context menu from the gutter (next to the line number in the editor). We chose this line because it follows the script lines where the first address is removed, so at this point (just before invoking the File menu to close the application), the first address should be that of "Jane Doe". The screenshot shows the verifications that were entered using the Squish IDE during recording. Our additional verifications will follow them. (Note that your line number may be different if you recorded the test in a different way, for example, using keyboard shortcuts rather than clicking menu items.)

Having set the breakpoint, we now run the test as usual by clicking the Run Test Case ( ) button, or by clicking the Run > Run Test Case menu option. Unlike a normal test run the test will stop when the breakpoint is reached, and Squish's main window will reappear (which will probably obscure the AUT). At this point the Squish IDE will automatically switch to the Test Debugging Perspective.

) button, or by clicking the Run > Run Test Case menu option. Unlike a normal test run the test will stop when the breakpoint is reached, and Squish's main window will reappear (which will probably obscure the AUT). At this point the Squish IDE will automatically switch to the Test Debugging Perspective.

Perspectives and Views

The Squish IDE works just like the Eclipse IDE. If you aren't used to Eclipse, it is crucial to understand the following key concepts: Views and Perspectives. In Eclipse, and therefore in the Squish IDE, a View is essentially a child window, such as a dock window or a tab in an existing window. A Perspective is a collection of views arranged together. Both are accessible through the Window menu.

The Squish IDE is supplied with the following perspectives:

- Test Management Perspective that the Squish IDE starts with, and that is shown in all previous screenshots

- Test Debugging Perspective

- Spy Perspective

You can modify these perspectives to show additional views, to hide views that you don't want, or to create your own perspectives with exactly the views you want.

If you notice all of your Views change dramatically, it just means that the perspective changed. Use the Window menu to change back to the perspective you want. Keep in mind, Squish automatically changes perspectives to reflect the current situation, so you should not need to change perspective manually very often.

When Squish stops at a breakpoint, the Squish IDE automatically changes to the Test Debugging Perspective. The perspective shows the Variables view, the Editor view, the Debug view, the Application Objects view, and the Properties view, Methods view, and Test Results view.

The normal Test Management Perspective can be returned to at any time by choosing it from the Window menu (or by clicking its toolbar button), although the Squish IDE will automatically return to it if you Terminate( ) or Resume(

) or Resume( ) to completion.

) to completion.

Inserting Verification Points

As the screenshot below shows, when Squish stops at a breakpoint the Squish IDE automatically changes to the Test Debugging Perspective. The perspective shows the Variables view, the Editor view, the Debug view, the Application Objects view, and the Properties view, Methods view, and Test Results view.

To insert a verification point we can expand items in the Application Objects view until we find the object we want to verify, or we can use the Object Picker ( ) to visually select it. In this example we want to verify the

) to visually select it. In this example we want to verify the NSTableView's first row's texts, so we expand the "Address Book - MyAddresses_adr_NSWindow_0" item, and its child items until we find the NSTableView, and within that the item we are interested in. Once we click the item object its properties are shown in the Properties view as the screenshot shows.

The normal Test Management Perspective can be returned to at any time by choosing it from the Window menu (or by clicking its toolbar button), although the Squish IDE will automatically return to it if you stop the script or run it to completion.

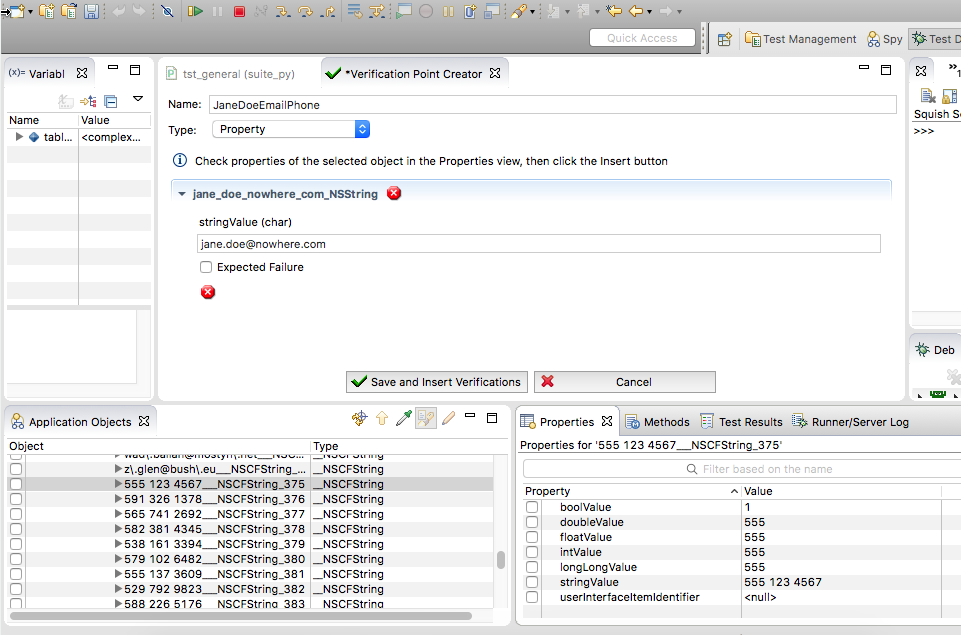

Here, we can see that the stringValue property of the first item in the table has the value "Jane"; we already have a verification for this that we inserted during recording. Scroll down so that you can see the corresponding (i.e., first) email address (the jane.doe@nowhere.com_NSCFString_250 item). To make sure that this is verified every time the test is run, select (without checking the box) this object in the Application Objects view to make its properties appear in the Properties view, and then click the stringValue property to check its check box. After it is checked, the Verification Point Creator view appears as shown in the screenshot.

After the property is selected, the verification point has not yet been added to the test script. We could easily add it by clicking the  Save and Insert Verifications button, but before doing that, set the Type of the verification to Property, since the combobox remembers the previously selected VP type. Choosing a meaningful name for the VP is also a good idea at this time. Otherwise we get names like VP1 and VP2, etc.

Save and Insert Verifications button, but before doing that, set the Type of the verification to Property, since the combobox remembers the previously selected VP type. Choosing a meaningful name for the VP is also a good idea at this time. Otherwise we get names like VP1 and VP2, etc.

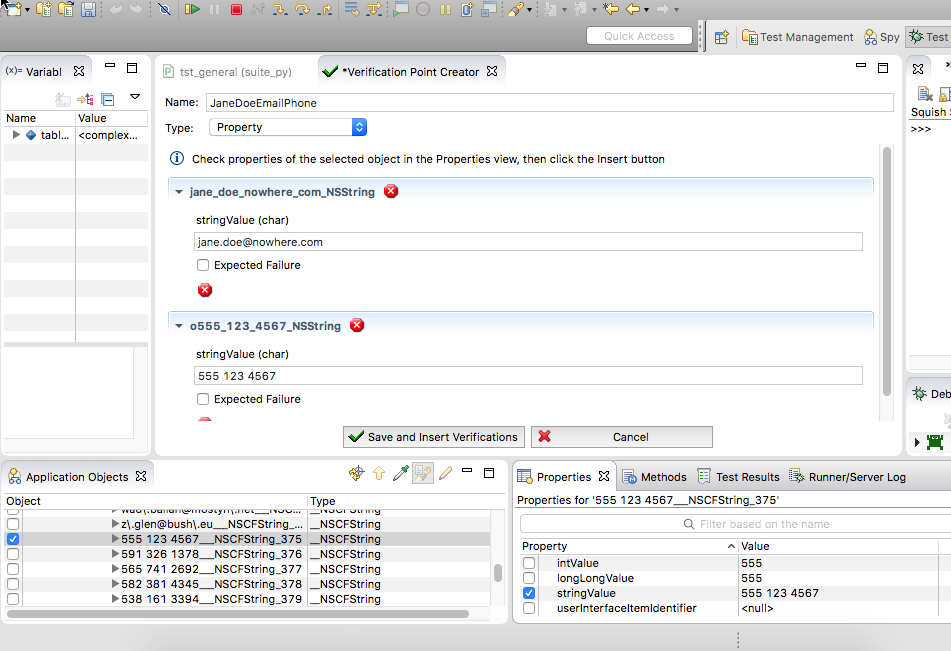

We'll add one more thing to be verified before we insert it into the script.

Scroll down and click the first phone number item (the 555 123 4567_NSCFString_375 item in the Application Objects view; then check its stringValue property in the Properties view. Now both verifications will appear in the Verification Point Creator view as the next screenshot shows.

We have now said that we expect these properties to have the values shown, that is, an email address of "jane.doe@nowhere.com" and phone number of "555 123 4567". We must click the  Save and Insert Verifications button to actually insert the verification point, so do that now.

Save and Insert Verifications button to actually insert the verification point, so do that now.

We don't need to continue running the test now, so we can either stop running the test at this point (by clicking the Stop toolbar button), or we can continue (by clicking the Resume button).

Once we have finished inserting verifications and stopped or finished running the test we should now disable the break point. Just Ctrl+Click the break point and click the Disable Breakpoint menu option in the context menu. We are now ready to run the test without any breakpoints but with the verification points in place. Click the Run Test Case ( ) button. This time we will get some test results—as the screenshot shows—one of which we have expanded to show its details. (We have also selected the line of code that Squish inserted to perform the verification—notice that the name you picked for the VP is used here).

) button. This time we will get some test results—as the screenshot shows—one of which we have expanded to show its details. (We have also selected the line of code that Squish inserted to perform the verification—notice that the name you picked for the VP is used here).

This particular verification point is stored as an XML file, containing two property comparisons for email, and phone number of the newly inserted entry. You can see it in the Test Case Resources window in the VPs tab, as well as open it in an editor from there.

Manually Written Property Verifications

Another way to insert verification points is to write the code manually. We can add our own calls to Squish's test. functions, such as test.compare and test.verify in an existing script.

- Set a breakpoint where we intend on adding our verifications.

- Run Test Case (

) until it stops there.

) until it stops there. - Use the Object Picker (

) or navigate in the Application Objects tree for the the object we want to verify.

) or navigate in the Application Objects tree for the the object we want to verify. - Right click the Application Object entry and select the Copy Symbolic Name context menu option—this adds the object to the Object Map if necessary.

Now we can edit the test script, paste name into the script where we need to find the object.

(Don't forget to disable the break point once it isn't needed any more.)

For this manual verification, we want to check the number of addresses present in the table after reading in the MyAddresses.adr file, then after the new address is added, and finally after the first address is removed. The screenshot shows two of the lines of code we entered to get one of these three verifications, plus the results of running the test script.

We begin by retrieving a reference to the object we are interested in, using waitForObject().

When writing scripts by hand, we use Squish's test module's functions to verify conditions at certain points during our test script's execution. As the screenshot (and the code snippets below) show, we begin by retrieving a reference to the object we are interested in. Using the Object waitForObject(objectOrName) function is standard practice for manually written test scripts. This function waits for the object to be available (i.e., visible and enabled), and then returns a reference to it. (Otherwise it times out and raises a catchable exception.) We then use this reference to access the item's properties and methods—in this case the NSTableView's numberOfRows method—and verify that the value is what we expect it to be using the Boolean test.verify(condition) function. (Incidentally, we got the name for the object from a later line so we didn't need to set a breakpoint and manually add the table's name to the Object Map to ensure that Squish would remember it in this particular case because Squish had already added it during the test recording.)

Here is the code we entered manually.

table = waitForObject(names.address_Book_MyAddresses_adr_NSTableView)

test.compare(table.numberOfRows(), 125) var table = waitForObject(names.addressBookMyAddressesAdrNSTableView);

test.compare(table.numberOfRows(), 125); my $table = waitForObject($Names::address_book_myaddresses_adr_nstableview);

test::compare($table->numberOfRows(), 125); table = waitForObject(Names::Address_Book_MyAddresses_adr_NSTableView)

Test.compare(table.numberOfRows(), 125)The coding pattern is very simple: we retrieve a reference to the object we are interested in and then verify its properties using one of Squish's verification functions. And we can, of course, call methods on the object to interact with it if we wish.

For more examples of manually written tests, see Creating Tests by Hand, How to Create Test Scripts, and How to Test Applications - Specifics.

Test Results

After each test run finishes, the test results—including those for the verification points—are shown in the Test Results view at the bottom of the Squish IDE.

This is a detailed report of the test run and would also contain details of any failures or errors, etc. If you click on a Test Results item, the Squish IDE highlights the script line which generated it. If you expand the item, you can see additional details of it.

Squish's interface for reporting test results is very flexible. The default report generator simply prints the results to stdout when Squish is run from the command line, or to the Test Results view when Squish IDE is being used. You can save the test results from the Squish IDE as XML by right clicking on the Test Results and choosing the Export Results menu option. For a list of report generators, see squishrunner –reportgen: Generating Reports.

It is possible to Upload the Results to Test Center, where they are stored in a database for analysis later.

Creating Tests by Hand

Now that we have seen how to record a test and modify it by inserting verification points, we are ready to see how to create tests manually. The easiest way to do this is to modify and refactor recorded tests, although it is also perfectly possible to create manual tests from scratch.

For each object of interest, we need a Symbolic or Real Name to access it.

If we have not interacted yet with the object of interest, we can get a name for it this way.

- click the Launch AUT (

) toolbar button. This starts the AUT and switches to the Spy Perspective. We can then interact with the AUT until the object we are interested in is visible.

) toolbar button. This starts the AUT and switches to the Spy Perspective. We can then interact with the AUT until the object we are interested in is visible. - From the Application Objects, use the Object Picker (

) or tree navigation to choose the desired object.

) or tree navigation to choose the desired object. - use the context menu to Add to Object Map or Copy (Symbolic | Real) Name to Clipboard (so that we can paste it into our test script).

We can view the Object Map by clicking the Object Map( ) toolbar button, or from the Script Editor context menu, Open Symbolic Name when right-clicking on an object name in the script editor.

) toolbar button, or from the Script Editor context menu, Open Symbolic Name when right-clicking on an object name in the script editor.

Every application object that Squish interacts with is listed here, either as a top-level object, or as a child object (the view is a tree view).

We can retrieve the symbolic name used by Squish in recorded scripts by right-clicking the object we are interested in and then clicking the context menu's Copy Object Name (to get the Symbolic Name variable) or Copy Real Name (to get the actual key-value pairs stored in the variable). This is useful for when we want to modify existing test scripts or when we want to create test scripts from scratch, as we will see later on in the tutorial.

Modifying and Refactoring Recorded Tests

Suppose we want to test the AUT's Add functionality by adding three new names and addresses. We could of course record such a test but it is just as easy to do everything in code. The steps we need the test script to do are:

- click File > New to create a new address book,

- for each new name and address, click Edit > Add, then fill in the details, and click OK.

- File > Quit without saving.

We want to verify at the start that there are no rows of data, and at the end that there are three rows. We will refactor as we go, to make our code as neat and modular as possible.

First, we must create a new test case. Click New Script Test Case ( ) and set the test case's name to be

) and set the test case's name to be tst_adding.

The first thing we need is a way to start the AUT and then invoke a menu option. Here are the first few lines from the recorded tst_general script:

import names

import os

def main():

startApplication('"' + os.environ["SQUISH_PREFIX"] + '/examples/mac/addressbook/SquishAddressBook"')

activateItem(waitForObject(names.file_NSMenuItem))

activateItem(waitForObject(names.open_NSMenuItem))import * as names from 'names.js';

function main()

{

startApplication('"' + OS.getenv("SQUISH_PREFIX") + '/examples/mac/addressbook/SquishAddressBook"');

activateItem(waitForObject(names.fileNSMenuItem));

activateItem(waitForObject(names.openNSMenuItem));require 'names.pl';

sub main

{

startApplication("\"$ENV{'SQUISH_PREFIX'}/examples/mac/addressbook/SquishAddressBook\"");

activateItem(waitForObject($Names::file_nsmenuitem));

activateItem(waitForObject($Names::open_nsmenuitem));require 'squish'

require 'names'

include Squish

def main

startApplication("\"#{ENV['SQUISH_PREFIX']}/examples/mac/addressbook/SquishAddressBook\"")

activateItem(waitForObject(Names::File_NSMenuItem))

activateItem(waitForObject(Names::Open_NSMenuItem))The pattern in the code is simple: start the AUT, then wait for the File menu to appear, then activate the File menu; wait for the menu item, then activate the menu item. In both cases we have used the Object waitForObject(objectOrName) and activateItem(objectOrName) functions that we've already seen.

If you look at the recorded test (tst_general) or in the Object Map you will see that Squish sometimes uses different names for the same things. For example, the window is identified in two different ways, initially as AddressBook_Untitled_NSWindow, but if the user clicks File > Open and opens the MyAddresses.adr file, the window is then identified as AddressBook_MyAddresses_adr_NSWindow. The reason for this is that Squish needs to uniquely identify every object in a given context, and it uses whatever information it has to hand. So in the case of identifying Main Windows (and their children), Squish uses the window title text to give it some context. (For example, an application's File or Edit menus may have different options depending on whether a file is loaded and what state the application is in.)

Naturally, when we write test scripts we don't want to have to know or care which particular variation of a name to use, and Squish supports this need by providing alternative naming schemes, as we will see shortly.

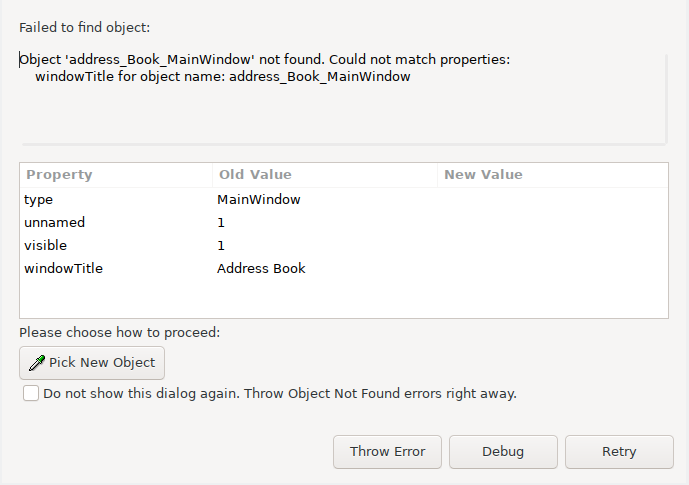

Object Not Found Dialog

If the AUT appears to freeze during test execution, wait for Squish to time out the AUT (about 20 seconds), and show the Object Not Found dialog, indicating an error like this:

This usually means that Squish doesn't have an object with the given name, or property values, in the Object Map. From here, we can Pick a new object, Debug, Throw Error or, after picking a new object, Retry.

Picking a new object will update the object map entry for the symbolic name. In addition to the Object Picker ( ), we can use the Spy's Application Objects view to locate the objects we are interested in and use the Add to the Object Map context menu action to to access their real or symbolic names.

), we can use the Spy's Application Objects view to locate the objects we are interested in and use the Add to the Object Map context menu action to to access their real or symbolic names.

Naming is important because it is probably the part of writing scripts that leads to the most error messages, usually of the object ... not found kind shown above. Once we have identified the objects to access in our tests, writing test scripts using Squish is very straightforward. Especially, as Squish most likely supports the scripting language you are most familiar with.

We are now almost ready to write our own test script. It is probably easiest to begin by recording a dummy test. So click File > New Test Case and set the test case's name to be tst_dummy. Then click the dummy test case's Record ( ). Once the AUT starts, click File > New, then click the (empty) table, then click Add and add an item, then press Return or click OK. Finally, click SquishAddressBook > Quit Squish Address Book to finish, and say "No" to saving changes. Then replay this test just to confirm that everything works okay. The sole purpose of this is to make sure that Squish adds the necessary names to the Object Map since it is probably quicker to do it this way than to use the Spy for every object of interest. After replaying the dummy test you can delete it if you want to.

). Once the AUT starts, click File > New, then click the (empty) table, then click Add and add an item, then press Return or click OK. Finally, click SquishAddressBook > Quit Squish Address Book to finish, and say "No" to saving changes. Then replay this test just to confirm that everything works okay. The sole purpose of this is to make sure that Squish adds the necessary names to the Object Map since it is probably quicker to do it this way than to use the Spy for every object of interest. After replaying the dummy test you can delete it if you want to.

With all the object names we need in the Object Map we can now write our own test script completely from scratch. We will start with the main function, and then we will look at the supporting functions that the main function uses.

import names

import os

def main():

startApplication('"' + os.environ["SQUISH_PREFIX"] + '/examples/mac/addressbook/SquishAddressBook"')

table = waitForObject(names.address_Book_Untitled_NSTableView)

mouseClick(waitForObject(names.address_Book_Untitled_New_NSToolbarItem))

test.verify(table.numberOfRows() == 0)

data = [("Andy", "Beach", "andy.beach@nowhere.com", "555 123 6786"),

("Candy", "Deane", "candy.deane@nowhere.com", "555 234 8765"),

("Ed", "Fernleaf", "ed.fernleaf@nowhere.com", "555 876 4654")]

for oneNameAndAddress in data:

addNameAndAddress(oneNameAndAddress)

test.compare(table.numberOfRows(), len(data))

closeWithoutSaving()import * as names from 'names.js';

function main()

{

startApplication('"' + OS.getenv("SQUISH_PREFIX") + '/examples/mac/addressbook/SquishAddressBook"');

var table = waitForObject(names.addressBookUntitledNSTableView);

mouseClick(waitForObject(names.addressBookUntitledNewNSToolbarItem));

test.verify(table.numberOfRows() == 0);

var data = new Array(

new Array("Andy", "Beach", "andy.beach@nowhere.com", "555 123 6786"),

new Array("Candy", "Deane", "candy.deane@nowhere.com", "555 234 8765"),

new Array("Ed", "Fernleaf", "ed.fernleaf@nowhere.com", "555 876 4654"));

for (var row = 0; row < data.length; ++row)

addNameAndAddress(data[row]);

test.compare(table.numberOfRows(), data.length);

closeWithoutSaving();

}require 'names.pl';

sub main

{

startApplication("\"$ENV{'SQUISH_PREFIX'}/examples/mac/addressbook/SquishAddressBook\"");

my $table = waitForObject($Names::address_book_untitled_nstableview);

mouseClick(waitForObject($Names::address_book_untitled_new_nstoolbaritem));

test::verify($table->numberOfRows() == 0);

my @data = (["Andy", "Beach", "andy.beach\@nowhere.com", "555 123 6786"],

["Candy", "Deane", "candy.deane\@nowhere.com", "555 234 8765"],

["Ed", "Fernleaf", "ed.fernleaf\@nowhere.com", "555 876 4654"]);

foreach $oneNameAndAddress (@data) {

addNameAndAddress(@{$oneNameAndAddress});

}

test::compare($table->numberOfRows(), scalar(@data));

closeWithoutSaving();

}require 'squish'

require 'names'

include Squish

def main

startApplication("\"#{ENV['SQUISH_PREFIX']}/examples/mac/addressbook/SquishAddressBook\"")

table = waitForObject(Names::Address_Book_Untitled_NSTableView)

mouseClick(waitForObject(Names::Address_Book_Untitled_New_NSToolbarItem))

Test.verify(table.numberOfRows() == 0)

data = [["Andy", "Beach", "andy.beach@nowhere.com", "555 123 6786"],

["Candy", "Deane", "candy.deane@nowhere.com", "555 234 8765"],

["Ed", "Fernleaf", "ed.fernleaf@nowhere.com", "555 876 4654"]]

data.each do |oneNameAndAddress|

addNameAndAddress(oneNameAndAddress)

end

Test.compare(table.numberOfRows(), data.length)

closeWithoutSaving

endWe begin by starting the application with a call to the ApplicationContext startApplication(autName) function. The name we pass as a string is the name registered with Squish (normally the name of the executable). Then we obtain a reference to the NSTableView. The object name we used was not put in the Object Map when the tst_general test case was recorded, so we recorded a dummy test to make sure the name was added—we could just as easily have used the Spy of course. We then copied the name from the Object Map into our code. The Object waitForObject(objectOrName) function waits until an object is ready (visible and enabled) and returns a reference to it—or it times out and raises a catchable exception. We have used a symbolic name to access the table—these are the names that Squish uses when recording tests—rather than a real/multi-property name. It is best to use symbolic names where possible because if any AUT object name changes, with symbolic names we just have to update the Object Map, without needing to change our test code. Once we have the table reference we can use it to access any of the NSTableView's public methods and properties.

Once we have started the AUT and obtained a reference to the NSTableView, we tell Squish to click the New toolbar button to create a new empty address book. Next, we verify that the table's row count is 0. The Boolean test.verify(condition) function is useful when we simply want to verify that a condition is true rather than compare two different values. (For Tcl we usually use the Boolean test.compare(value1, value2) function rather than the Boolean test.verify(condition) function simply because it is slightly simpler to use in Tcl.)

Next, we create some sample data and call a custom addNameAndAddress() function to populate the table with the data using the AUT's Add sheet. Then we again compare the table's row count, this time to the number of rows in our sample data. And finally we call a custom closeWithoutSaving function to terminate the application.

We will now review both of the supporting functions, so as to cover all the code in the tst_adding test case, starting with addNameAndAddress().

def addNameAndAddress(oneNameAndAddress):

mouseClick(waitForObject(names.address_Book_Untitled_Add_NSToolbarItem))

type(waitForObject(names.add_Address_NSTextField), oneNameAndAddress[0])

type(waitForObject(names.add_Address_NSTextField_2), oneNameAndAddress[1])

type(waitForObject(names.add_Address_NSTextField_3), oneNameAndAddress[2])

type(waitForObject(names.add_Address_NSTextField_4), oneNameAndAddress[3])

mouseClick(waitForObject(names.add_Address_Add_NSButton))function addNameAndAddress(oneNameAndAddress)

{

mouseClick(waitForObject(names.addressBookUntitledAddNSToolbarItem));

type(waitForObject(names.addAddressNSTextField), oneNameAndAddress[0]);

type(waitForObject(names.addAddressNSTextField_2), oneNameAndAddress[1]);

type(waitForObject(names.addAddressNSTextField_3), oneNameAndAddress[2]);

type(waitForObject(names.addAddressNSTextField_4), oneNameAndAddress[3]);

mouseClick(waitForObject(names.addAddressAddNSButton));

}sub addNameAndAddress

{

my (@oneNameAndAddress) = @_;

mouseClick(waitForObject($Names::address_book_untitled_add_nstoolbaritem));

type(waitForObject($Names::add_address_nstextfield), $oneNameAndAddress[0]);

type(waitForObject($Names::add_address_nstextfield_2), $oneNameAndAddress[1]);

type(waitForObject($Names::add_address_nstextfield_3), $oneNameAndAddress[2]);

type(waitForObject($Names::add_address_nstextfield_4), $oneNameAndAddress[3]);

mouseClick(waitForObject($Names::add_address_add_nsbutton));

}def addNameAndAddress(oneNameAndAddress)

mouseClick(waitForObject(Names::Address_Book_Untitled_Add_NSToolbarItem))

type(waitForObject(Names::Add_Address_NSTextField), oneNameAndAddress[0])

type(waitForObject(Names::Add_Address_NSTextField_2), oneNameAndAddress[1])

type(waitForObject(Names::Add_Address_NSTextField_3), oneNameAndAddress[2])

type(waitForObject(Names::Add_Address_NSTextField_4), oneNameAndAddress[3])

mouseClick(waitForObject(Names::Add_Address_Add_NSButton))

endFor each set of name and address data we click Add to pop up the Add sheet. Then, for each value received, we populate the appropriate field by waiting for the relevant NSTextField to be ready and then typing in the text using the type(objectOrName, text) function. Finally, we click the sheet's Add button. We got the line at the heart of the function by copying it from the recorded tst_general test and simply parametrizing it by the field name and text. Similarly, we copied the code for clicking the Add button from the tst_general test case's code.

def closeWithoutSaving():

type(waitForObject(names.address_Book_Untitled_NSTableView), "<Command+q>")

mouseClick(waitForObject(names.save_Changes_Don_t_Save_NSButton))function closeWithoutSaving()

{

type(waitForObject(names.addressBookUntitledNSTableView), "<Command+q>");

mouseClick(waitForObject(names.saveChangesDonTSaveNSButton));

}sub closeWithoutSaving

{

type(waitForObject($Names::address_book_untitled_nstableview), "<Command+q>");

mouseClick(waitForObject($Names::save_changes_don_t_save_nsbutton));

}def closeWithoutSaving

type(waitForObject(Names::Address_Book_Untitled_NSTableView), "<Command+q>")

mouseClick(waitForObject(Names::Save_Changes_Don_t_Save_NSButton))

endHere we quit the application by pressing Command+Q and then click the "save changes" dialog's Don't Save button. The last line was copied from the recorded test.

The entire test is about 25 lines of code—and would be even less if we put some of the common functions (such as closeWithoutSaving()) in a shared script. And much of the code was copied directly from the recorded test, and in some cases parametrized.

This should be sufficient to give a flavor of writing test scripts for an AUT. Keep in mind that Squish provides far more functionality than we used here. (All of which is covered in the API Reference and the Tools Reference.) And Squish also provides access to the entire public APIs of the AUT's objects.

However, one aspect of the test case is not very satisfactory. Although embedding test data as we did here is sensible for small amounts, it is rather limiting, especially when we want to use a lot of test data. Also, we didn't test any of the data that was added to see if it correctly ended up in the NSTableView. In the next section, we will create a new version of this test, only this time we will pull in the data from an external data source, and check that the data we add to the NSTableView is correct.

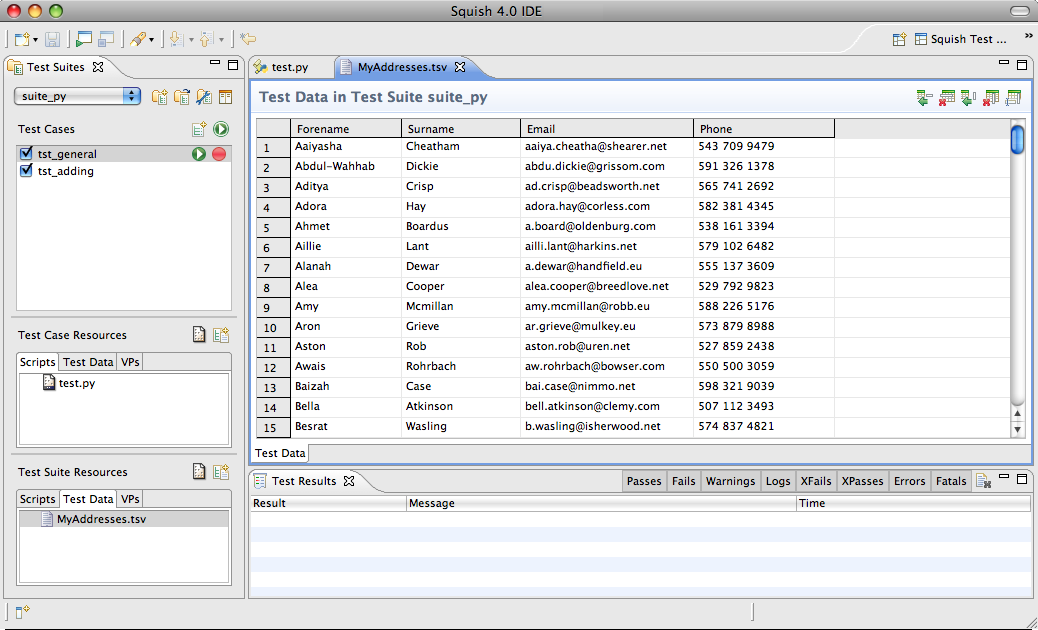

Creating Data Driven Tests

In the previous section we had hard-coded names and addresses in our test. But what if we want to test lots of data? Or what if we want to change the data without having to change our test script's source code. One approach is to import a dataset into Squish and use the dataset as the source of the values we insert into our tests. Squish can import data in .tsv (tab-separated values format), .csv (comma-separated values format), .xls, or .xlsx (Microsoft Excel spreadsheet formats).

Note: Both .csv and .tsv files are assumed to use the Unicode UTF-8 encoding, which is used for all test scripts.

We want to add a test data file to our test suite. We can copy MyAddresses.tsv directly into the shared/testdata directory, or we can import it using the Squish IDE.

To import, we click File > Import Test Resource to pop-up the Import Squish Resource dialog. Inside the dialog, click the Browse button to choose the file to import (you can find this file already added to our example test suites). Make sure that the Import As combobox is set to "TestData".

By default the Squish IDE will import the test data just for the current test case, but we want the test data to be available to all the test suite's test cases: to do this check the Copy to Test Suite for Sharing radio button. Next, click the Finish button.

You should now see the file listed in the Test Suite Resources view (in the Test Data tab), and if you click the file's name it will be shown in an Editor view. The screenshot shows Squish IDE after some test data has been opened.

Adding a Test Case

Although in real life we would modify our tst_adding test case to use the test data, for the purpose of the tutorial we will make a new test case called tst_adding_data that is a copy of tst_adding and which we will modify to make use of the test data.

The only function we have to change is main, where instead of iterating over hard-coded items of data, we iterate over all the records in the dataset. We also need to update the expected row count at the end since we are adding a lot more records now, and we will also add a function to verify each record that's added.

import names

import os

def main():

startApplication('"' + os.environ["SQUISH_PREFIX"] + '/examples/mac/addressbook/SquishAddressBook"')

table = waitForObject(names.address_Book_Untitled_NSTableView)

mouseClick(waitForObject(names.address_Book_Untitled_New_NSToolbarItem))

test.verify(table.numberOfRows() == 0)

limit = 10 # To avoid testing 100s of rows

for row, record in enumerate(testData.dataset("MyAddresses.tsv")):

forename = testData.field(record, "Forename")

surname = testData.field(record, "Surname")

email = testData.field(record, "Email")

phone = testData.field(record, "Phone")

addNameAndAddress((forename, surname, email, phone)) # pass a single tuple

checkNameAndAddress(row, table, record)

if row > limit:

break

test.compare(table.numberOfRows(), row + 1)

closeWithoutSaving()import * as names from 'names.js';

function main()

{

startApplication('"' + OS.getenv("SQUISH_PREFIX") + '/examples/mac/addressbook/SquishAddressBook"');

var table = waitForObject(names.addressBookUntitledNSTableView);

mouseClick(waitForObject(names.addressBookUntitledNewNSToolbarItem));

test.verify(table.numberOfRows() == 0);

var limit = 10; // To avoid testing 100s of rows since that would be boring

var records = testData.dataset("MyAddresses.tsv");

for (var row = 0; row < records.length; ++row) {

var record = records[row];

var forename = testData.field(record, "Forename");

var surname = testData.field(record, "Surname");

var email = testData.field(record, "Email");

var phone = testData.field(record, "Phone");

addNameAndAddress(new Array(forename, surname, email, phone));

checkNameAndAddress(row, table, record);

if (row > limit)

break;

}

test.compare(table.numberOfRows(), row + 1);

closeWithoutSaving();

}require 'names.pl';

sub main

{

startApplication("\"$ENV{'SQUISH_PREFIX'}/examples/mac/addressbook/SquishAddressBook\"");

my $table = waitForObject($Names::address_book_untitled_nstableview);

mouseClick(waitForObject($Names::address_book_untitled_new_nstoolbaritem));

test::verify($table->numberOfRows() == 0);

my $limit = 10; # To avoid testing 100s of rows since that would be boring

my @records = testData::dataset("MyAddresses.tsv");

my $row = 0;

for (; $row < scalar(@records); ++$row) {

my $record = $records[$row];

my $forename = testData::field($record, "Forename");

my $surname = testData::field($record, "Surname");

my $email = testData::field($record, "Email");

my $phone = testData::field($record, "Phone");

addNameAndAddress($forename, $surname, $email, $phone);

checkNameAndAddress($row, $table, $record);

if ($row > $limit) {

last;

}

}

test::compare($table->numberOfRows(), $row + 1);

closeWithoutSaving();

}require 'squish'

require 'names'

include Squish

def main

startApplication("\"#{ENV['SQUISH_PREFIX']}/examples/mac/addressbook/SquishAddressBook\"")

table = waitForObject(Names::Address_Book_Untitled_NSTableView)

mouseClick(waitForObject(Names::Address_Book_Untitled_New_NSToolbarItem))

Test.verify(table.numberOfRows() == 0)

limit = 10 # To avoid testing 100s of rows

rows = 0

TestData.dataset("MyAddresses.tsv").each_with_index do

|record, row|

forename = TestData.field(record, "Forename")

surname = TestData.field(record, "Surname")

email = TestData.field(record, "Email")

phone = TestData.field(record, "Phone")

addNameAndAddress([forename, surname, email, phone]) # pass as a single Array

checkNameAndAddress(row, table, record)

break if row > limit

rows += 1

end

Test.verify(table.numberOfRows() == rows + 1)

closeWithoutSaving

endSquish provides access to test data through its testData module's functions—here we used the Dataset testData.dataset(filename) function to access the data file and make its records available, and the String testData.field(record, fieldName) function to retrieve each record's individual fields.

Having used the test data to populate the NSTableView we want to be confident that the data in the table is the same as what we have added, so that's why we added the checkNameAndAddress function. We also added a limit to how many records we would compare, just to make the test run faster.

def checkNameAndAddress(row, table, record):

for column in range(len(testData.fieldNames(record))):

cellName = {'rowNumber': row, 'columnNumber': column, 'tableView': names.address_Book_Untitled_NSTableView, 'type': 'NSString'}

cell = waitForObject(cellName)

test.compare(cell.stringValue, testData.field(record, column))function checkNameAndAddress(row, table, record)

{

for (var column = 0; column < testData.fieldNames(record).length; ++column) {

var cellName = {'rowNumber': row, 'columnNumber': column, 'tableView': names.addressBookUntitledNSTableView, 'type': 'NSString'};

var cell = waitForObject(cellName);

test.compare(cell.stringValue, testData.field(record, column));

}

}def checkNameAndAddress(row, table, record)

for column in 0...TestData.fieldNames(record).length

cellName = {:rowNumber => row, :columnNumber => column, :tableView => Names::Address_Book_Untitled_NSTableView, :type => 'NSString'}

cell = waitForObject(cellName)

Test.compare(cell.stringValue, TestData.field(record, column))

end

endThis function accesses the give NSTableView row and extracts each of its columns' values. We use Squish's SequenceOfStrings testData.fieldNames(record) function to get a column count and then use the Boolean test.compare(value1, value2) function to check that each value in the table is the same as the value in the test data we used.

As we mentioned earlier, the symbolic names Squish uses for menus and menu items (and other objects) can vary depending on the context, and often with the start of the name derived from the window's title. For applications that put the current filename in the title—such as the Address Book example—names will include the filename, and we must account for this.

In the case of the Address Book example, the main window's title is "Address Book" (at startup), or "Address Book - Unnamed" (after File > New , but before File > Save or File > Save As), or "Address Book - filename" where the filename can of course vary. Our code accounts for all these cases by making use of real (multi-property) names.

Symbolic names embed various bits of information about an object and its type. Real names are represented by a brace enclosed list of space-separated key–value pairs. Every real name must specify the type property and at least one other property. Here we've used the rowNumber, columnNumber, tableView, and type properties to uniquely identify each cell in the table so that we can compare each cell's stringValue with the data used to populate it.

The screenshot show Squish's Test Summary log after the data-driven tests have been run.

Squish can also do keyword-driven testing. This is a bit more sophisticated than data-driven testing. See How to Do Keyword-Driven Testing.

Learning More

We have now completed the tutorial. Squish can do much more than we have shown here, but the aim has been to get you started with basic testing as quickly and easily as possible. The How to Create Test Scripts, and How to Test Applications - Specifics sections provide many more examples, including those that show how tests can interact with particular input elements, such as selects, select-ones, texts, and text-areas.

The API Reference and Tools Reference give full details of Squish's testing API and the numerous functions it offers to make testing as easy and efficient as possible. The time you invested will be repaid because you'll know what functionality Squish provides out of the box and can avoid reinventing things that are already available.

If you are interested in testing iPhone Apps, see Tutorial: Starting to Test iOS Applications.

Tutorial: Designing Behavior Driven Development (BDD) Tests

This tutorial will show you how to create, run, and modify Behavior Driven Development (BDD) tests for an example application. You will learn about Squish's most frequently used features. By the end of the tutorial you will be able to write tests for your own applications.

For this chapter we will use a simple address book application as our Application Under Test (AUT). It is called SquishAddressBook.app in your examples/addressbook folder. This is a very basic application that allows users to load an existing address book or create a new one, add, edit, and remove entries. The screenshot shows the application with a newly created, empty address book.

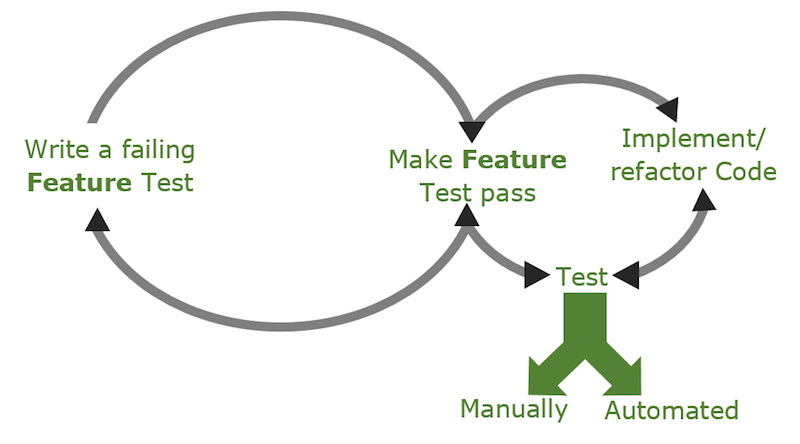

Introduction to Behavior Driven Development

Behavior-Driven Development (BDD) is an extension of the Test-Driven Development approach which puts the definition of acceptance criteria at the beginning of the development process as opposed to writing tests after the software has been developed. With possible cycles of code changes done after testing.

Behavior Driven Tests are built out of a set of Feature files, which describe product features through the expected application behavior in one or many Scenarios. Each Scenario is built out of a sequence of Steps which represent actions or verifications that need to be tested for that Scenario.

BDD focuses on expected application behavior, not on implementation details. Therefore BDD tests are described in a human-readable Domain Specific Language (DSL). As this language is not technical, such tests can be created not only by programmers, but also by product owners, testers or business analysts. Additionally, during the product development, such tests serve as living product documentation. For Squish usage, BDD tests shall be created using Gherkin syntax. The previously written product specification (BDD tests) can be turned into executable tests. This step by step tutorial presents automating BDD tests with Squish IDE support.

Gherkin syntax

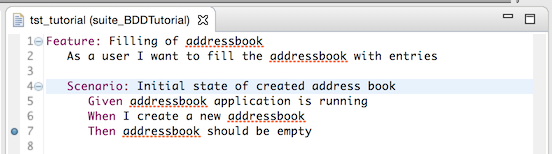

Gherkin files describe product features through the expected application behavior in one or many Scenarios. Here is an example showing the "Filling of addressbook" feature of the addressbook example application.

Feature: Filling of addressbook

As a user I want to fill the addressbook with entries

Scenario: Initial state of created address book

Given addressbook application is running

When I create a new addressbook

Then addressbook should have zero entries

Scenario: State after adding one entry

Given addressbook application is running

When I create a new addressbook

And I add a new person 'John','Doe','john@m.com','500600700' to address book

Then '1' entries should be present

Scenario: State after adding two entries

Given addressbook application is running

When I create a new addressbook

And I add new persons to address book

| forename | surname | email | phone |

| John | Smith | john@m.com | 123123 |

| Alice | Thomson | alice@m.com | 234234 |

Then '2' entries should be present

Scenario: Forename and surname is added to table

Given addressbook application is running

When I create a new addressbook

When I add a new person 'Bob','Doe','Bob@m.com','123321231' to address book

Then previously entered forename and surname shall be at the topMost of the above is free form text (does not have to be English). It's just the Feature/Scenario structure and the leading keywords like "Given", "And", "When" and "Then" that are fixed. Each of those keywords marks a Step defining preconditions, user actions and expected results. This application behavior specification can be passed to software developers to implement features, and at the same time it can be passed to software testers to implement automated tests.

Test Implementation

Creating Test Suite

First, we need to create a Test Suite. Start the Squish IDE and select File > New Test Suite. Follow the New Test Suite wizard, provide a Test Suite name, choose the Mac Toolkit, scripting language of your choice, and finally register Address Book application as AUT (if necessary).

Creating Test Case

Squish supports different types of Test Cases: "Script", "BDD" and "MBT". "Script" is the default. In order to create new "BDD Test Case", use the context menu by clicking on the expander next to New Script Test Case ( ) button and choosing the option New BDD Test Case. The Squish IDE will remember your choice and the "BDD Test Case" will become the default when clicking on the button in the future.

) button and choosing the option New BDD Test Case. The Squish IDE will remember your choice and the "BDD Test Case" will become the default when clicking on the button in the future.

The new BDD Test Case consists of a test.feature file (filled with a Gherkin template while creating a new BDD test case), a file named test.(py|js|pl|rb|tcl) which will drive the execution (there is no need to edit this file), and a Test Suite Resources file named shared/steps/steps.(py|js|pl|rb|tcl) where step implementation code will be placed.

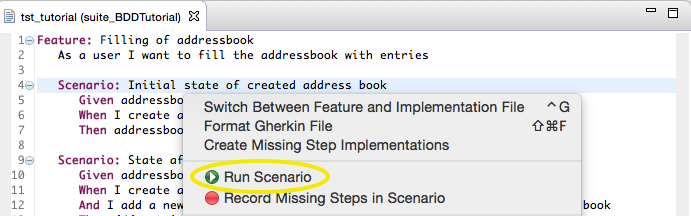

We need to replace the Gherkin template with a Feature for the addressbook example application. To do this, copy the Feature description below and paste it into the Feature file.

Feature: Filling of addressbook

As a user I want to fill the addressbook with entries

Scenario: Initial state of created address book

Given addressbook application is running

When I create a new addressbook

Then addressbook should have zero entriesWhen editing the test.feature file, a warning No implementation found is displayed for each undefined step. The implementations are in the steps subdirectory, in Test Case Resources, or in Test Suite Resources. Running our Feature test now will currently fail at the first step with a No Matching Step Definition and the following steps will be skipped.

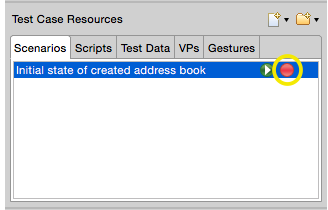

Recording Step Implementation

In order to record the Scenario, press the Record ( ) next to the respective

) next to the respective Scenario that is listed in the Scenarios tab in the Test Case Resources view.

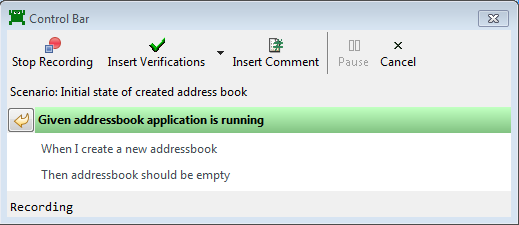

This will cause Squish to run the AUT so that we can interact with it. Additionally, the Control Bar is displayed with a list of all steps that need to be recorded. Now all interaction with the AUT or any verification points added to the script will be recorded under the currently recording step, Given the address book application is running (which is bolded in the Step list on the Control Bar). In order to verify that this precondition is met, we will add a Verification Point. To do this, click on Verify ( ) button in the Control Bar and then select Properties.

) button in the Control Bar and then select Properties.

As a result the Squish IDE is put into Spy mode which displays all Application Objects and their Properties in dockable Views. In the Application Objects view, select the main window item (Address Book - Untitled_NSWindow). Selecting it will update the Properties view on the right side. Next click on the checkbox in front of the property isVisible in the Properties View. Finally, click on the button  Save and Insert Verifications. The Squish IDE disappears and the Control Bar is shown again.

Save and Insert Verifications. The Squish IDE disappears and the Control Bar is shown again.

When we are done with each Step, we can move to the next undefined step (playing back the ones that were previously defined) by clicking on the Finish Recording Step( ) arrow button in the Control Bar that is located to the left of the current step.

) arrow button in the Control Bar that is located to the left of the current step.

Next, for the Step When I create a new address book, click on the New button ( ) in the toolbar of the addressbook application and click on the Finish Recording Step(

) in the toolbar of the addressbook application and click on the Finish Recording Step( ) in the Squish control bar, to finish recording and go to the next step.

) in the Squish control bar, to finish recording and go to the next step.

Finally, for the step the address book should be empty, verify that the table containing the address entries is empty. To record this verification, click on Verify ( ) while recording and select Properties. Now, in Application Objects, navigate or use the Object Picker (

) while recording and select Properties. Now, in Application Objects, navigate or use the Object Picker ( ) to select the table containing the address book entries (in our case this table is empty). You will notice that the

) to select the table containing the address book entries (in our case this table is empty). You will notice that the Table object does not provide a property for the number of rows. This information is not directly available. Therefore we need to modify the recorded code later on. To let Squish generate some test.compare() code for our step, insert a verification for a random property, for example alignment. Finally, click on the last Finish Recording Step( ) button.

) button.

As a result, Squish will generate the following step definitions in the steps.* file (in the Steps tab of the Test Suite Resources view):

@Given("the address book application is running")

def step(context):

startApplication('"' + os.environ["SQUISH_PREFIX"] + '/examples/mac/addressbook/SquishAddressBook"')

test.compare(waitForObjectExists(names.o_NSWindow).isVisible, 0)

@When("I create a new address book")

def step(context):

mouseClick(waitForObject(names.address_Book_Untitled_New_NSToolbarItem))

@Then("the address book should be empty")

def step(context):

#test.compare(waitForObjectExists(names.address_Book_Untitled_NSTableView).alignment, 0)

test.compare(waitForObjectExists(names.address_Book_Untitled_NSTableView).numberOfRows(), 0)Given("addressbook application is running", function(context) {

startApplication('"' + OS.getenv("SQUISH_PREFIX") + '/examples/mac/addressbook/SquishAddressBook"');

test.compare(waitForObjectExists(names.addressBookUntitledNSWindow).isVisible, 1);

});

When("I create a new addressbook", function(context) {

mouseClick(waitForObject(names.addressBookUntitledNewNSToolbarItem));

});

Then("addressbook should have zero entries", function(context) {

//test.compare((waitForObject(names.addressBookUntitledNSTableView)).alignment, 0);

test.compare((waitForObject(names.addressBookUntitledNSTableView)).numberOfRows(), 0);

});Given("the address book application is running", sub {

my $context = shift;

startApplication("\"$ENV{'SQUISH_PREFIX'}/examples/mac/addressbook/SquishAddressBook\"");

test::compare(waitForObjectExists($Names::address_book_untitled_nswindow)->isVisible, 1);

});

When("I create a new address book", sub {

my $context = shift;

mouseClick(waitForObject($Names::address_book_untitled_new_nstoolbaritem));

});

Then("the address book should be empty", sub {

my $context = shift;

#test::compare(waitForObjectExists($Names::address_book_untitled_nstableview)->alignment, 1);

test::compare(waitForObjectExists($Names::address_book_untitled_nstableview)->numberOfRows, 0);

});Given("the address book application is running") do |context|

startApplication("\"#{ENV['SQUISH_PREFIX']}/examples/mac/addressbook/SquishAddressBook\"")

Test.compare(waitForObjectExists(Names::O_NSWindow).isVisible, 0)

end

When("I create a new address book") do |context|

mouseClick(waitForObject(Names::Address_Book_Untitled_New_NSToolbarItem))

end

Then("the address book should be empty") do |context|

#Test.compare(waitForObjectExists(Names::Address_Book_Untitled_NSTableView).alignment, 0)

Test.compare(waitForObjectExists(Names::Address_Book_Untitled_NSTableView).numberOfRows(), 0)

endIn order to get the number of rows, we have to call a method of the underlying NSTableView object.

The application is automatically started at the beginning of the first step due to the recorded startApplication() call. At the end of each Scenario, the OnScenarioEnd hook is called, causing detach() to be called on the application context. Because the AUT was started with startApplication(), this causes it to terminate. This hook function is found in the file bdd_hooks.(py|js|pl|rb|tcl), which is located in the Scripts tab of the Test Suite Resources view. You can define additional hook functions there. For a list of all available hooks, please refer to Performing Actions During Test Execution Via Hooks.

@OnScenarioEnd

def OnScenarioEnd():

for ctx in applicationContextList():

ctx.detach()OnScenarioEnd(function(context) {

applicationContextList().forEach(function(ctx) { ctx.detach(); });

});OnScenarioEnd(sub {

foreach (applicationContextList()) {

$_->detach();

}

});OnScenarioEnd do |context| applicationContextList().each { |ctx| ctx.detach() } end

Step Parametrization

So far, our steps did not use any parameters and all values were hardcoded. Squish has different types of parameters like any, integer or word, allowing our step definitions to be more reusable. Let us add a new Scenario to our Feature file which will provide step parameters for both the Test Data and the expected results. Copy the below section into your Feature file.

Scenario: State after adding one entry

Given the address book application is running

When I create a new address book

And I add a new person 'John','Doe','john@m.com','500600700' to the address book

Then '1' entries should be presentAfter auto-saving the Feature file, the Squish IDE provides a hint that only 2 steps need to be implemented: When I add a new person 'John', 'Doe','john@m.com','500600700' to the address book and Then '1' entries should be present. The remaining steps already have a matching implementation.